© UNICEF/UN0640751/Dejongh. A 15-year-old survivor waits in a UNICEF transit centre in Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, where she receives temporary care and support.

On the International Day of Zero Tolerance, we summarise what impact evaluations are teaching us about FGM measurement

Authors: Josué Ango, Néné Barry, Horace Gninafon, Fatoumata Ki, Achille Mignondo Tchibozo, Amber Peterman, Daouda Sako, Manahil Siddiqi, and Florent Somda.

Over 230 million women and girls have experienced female genital mutilation (FGM) globally, with 4 million girls being subjected to this human rights violation every year, according to UNICEF statistics. Thanks to population-based surveys, we now have the data to track FGM progress, investigate hot spots and assess intervention entry points in high prevalence countries. Nonetheless, FGM has traditionally been under-researched when it comes to rigorous impact evaluation. Thus, despite some understanding of ‘what works’ – much more is needed.

A fundamental building block of understanding effective intervention strategies is the accurate, sensitive, context-appropriate and ethical measurement of FGM in surveys. Nonetheless, when carrying out impact evaluations, researchers may be concerned that FGM dynamics may be underestimated due to sensitivity, stigma, recall limitations, and the illegality of FGM, all of which keep the practice ‘hidden’ and discourage honest reporting.

These sources of bias also align with our own experiences collecting FGM data in impact evaluations as part of UNICEF, UNFPA and partners’ research teams. We found that questions on FGM attitudes, norms and behaviours are viewed as more sensitive than other topics, including violence against women or child marriage.

Why does FGM measurement in impact evaluation matter?

Let’s consider two stylised scenarios. First, suppose we are evaluating a community mobilisation intervention meant to change harmful gender and social norms towards FGM (as per our ongoing effort in Burkina Faso). If participants believe there is a ‘right’ or socially acceptable answer, they may be less willing to admit support for FGM—even if their views or behaviours have not changed. This could lead to an overestimation of program impacts.

Second, FGM may be so highly stigmatised that, regardless of programme exposure, almost no one reports the practice. In this scenario, we may lack statistical power and be unable to determine if the intervention worked – even if it did reduce FGM in practice. In fact, in this scenario, policymakers could believe that FGM is so low that resources could be dedicated to other efforts – and not to ending FGM. Thus, accurate data is essential for making sound recommendations on program design, investment, and scale-up.

Amidst these challenges, can impact evaluations meaningfully capture FGM dynamics? Evidence suggests that yes, it can! In honour of the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation (#EndFGM), we share emerging lessons on FGM measurement from our work and the broader evidence base.

Are survey responses on FGM experience valid? Medical verification suggests yes—with caveats.

A key question is whether survey responses on FGM experience can be trusted. While comparisons with objective measures (medical verification) are rare, the available evidence points to high overall agreement. For example, a recent impact evaluation in Sierra Leone surveyed over 3,500 mothers across 150 villages using the MICS-style questions on their daughters’ FGM status (Corno & La Ferrara 2022). Girls were also invited for a free health checkup at a mobile clinic where a nurse confirmed their status. Encouragingly, the two measures correlated “almost perfectly” across three rounds.

That said, previous studies in Sierra Leone and Sudan suggest that while prevalence figures might align, agreement on the type of FGM is often poor. One likely explanation is that when FGM is performed very young, women may have no knowledge, recall or terminology to describe their own experience, leading to reporting errors

Can FGM prevalence be captured accurately through ‘proxy reports?’ Yes, and potentially more accurately than self-reports

Women are often asked both about their own FGM status and that of their daughters’, which facilitates intergenerational comparison. How accurate are these proxy reports in comparison to self-reports? An impact evaluation in Ethiopia collected reports from over 3,000 fathers and mothers across 78 communities, asking about their daughters’ FGM status in separate interviews (Gichohi et al. 2025). Results show 97% concordance in responses. This is promising news – and a neat way to bolster confidence in reports.

In fact, a study in Senegal shows women’s proxy reports for their daughters may be more accurate than women’s self-reports (Weny et al. 2025). These findings underscore that caregiver responses for daughters can be a robust, and sometimes preferable, source of data.

Can respondents correctly estimate community support for FGM, and does it matter? Evidence is mixed.

A growing body of behavioural research shows that people around the world frequently misperceive gender norms (i.e., believe there is more support for a practice than there actually is). These perceptions matter because individuals may adjust their choices based on what they think others expect or do.

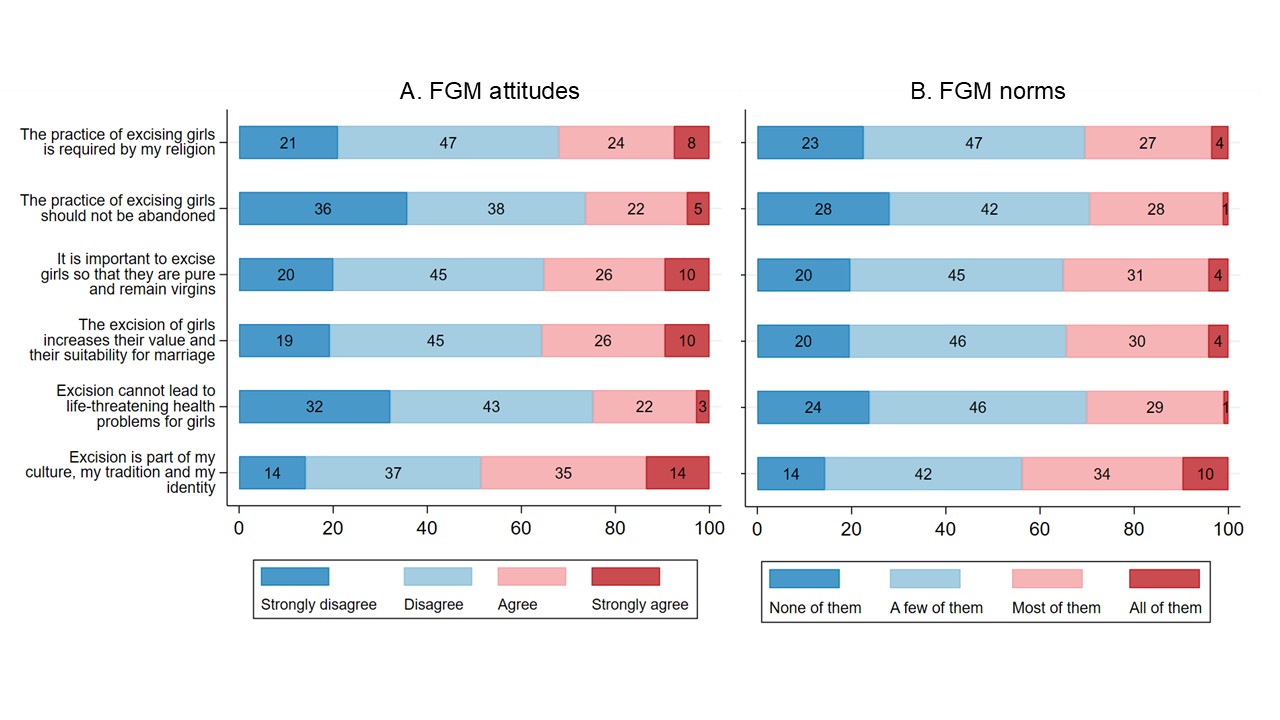

For example, in Ethiopia and Somalia, baseline surveys find that respondents systematically overestimate their communities’ support for FGM (Gichohi et al. 2025; Ferreira et al. 2024). However, in our baseline survey in Burkina Faso, levels of reported personal attitudes and perceived community norms are similar (see Figure 1).

Moreover, the effects of providing information to correct misperceived norms are mixed. In Ethiopia, revealing that nearby communities had abandoned support for FGM, had no effects on overall attitudes; although for fathers, it led to reductions in future intentions to cut their daughters. Meanwhile, in Somalia, informing participants that their own communities showed lower support for a more severe form of FGM (type III) reduced girls experiences of the same two years later, although it concurrently increased a less severe form of FGM (type I). Therefore, while correcting perceptions of harmful social norms is a promising area of exploration, practical challenges and messaging complexities require caution and reflection across contexts.

Figure 1. Comparison of FGM attitude and norm responses in Burkina Faso

Source: 7,500 caregivers across 150 communities in Burkina Faso; UNICEF & UNFPA, 2025 (not public, trial details here). Attitudes measure personal agreement with each statement; norms measure perceived agreement of other community members.

How does social desirability affect responses? More research is needed

Evaluation efforts often aim to unpack social desirability bias, as interventions may shift perceptions of the acceptability of FGM, and in turn, influence survey responses. However, evidence on the role of these biases is mixed. For example, the study from Sierra Leone examines interactions between a proxy scale for social desirability and daughters’ reported FGM, finding no meaningful correlation. This suggests that in some contexts, social desirability may not strongly distort reporting on FGM.

In contrast, the study in Ethiopia found that individuals with high social desirability scores are less likely to report a cut daughter. This aligns with findings on FGM attitudes and norms from our baseline survey in Burkina Faso. Overall, we believe more experimentation is needed to unpack how socially desirability matters – especially in settings with laws banning FGM and where existing social desirability scales may not resonate with contextually relevant behaviours.

Looking forward: Expanding innovative measures to capture FGM attitudes, norms and experiences accurately

Further methodological innovation is needed to unpack behavioural pathways in FGM decisions in ways that resonate with local customs. For example, an impact evaluation in Sudan piloted two complementary measurement innovations. First, interviewers documented the presence of henna on girls’ feet as a culturally specific proxy for recent FGM ceremonies. Second, a novel Implicit Association Test was developed to assess FGM attitudes (Vogt et al. 2016). In this test, audio recordings of positive and negative words were paired with caricatures of ‘cut’ and ‘uncut’ girls to capture respondents associated unconscious biases.

Other innovations being tested include UNICEF-led tools using vignettes, asking respondents to react to stylised stories about families facing decisions about cutting. These tools can be lengthier to administer, but surface trade-offs, reference groups, and perceived sanctions may not emerge through direct questioning. When designed well, these approaches can complement standard survey measures and strengthen learning about how and why change occurs.

Interest in rigorous impact evaluation to understand what works to prevent FGM has increased over the last years—and with it a renewed interest in measurement. This is very welcome. We still have much to learn about how questions and concepts should be tailored to different contexts and target groups. Meanwhile, the good news is that recent work broadly finds high accuracy, concordance and innovative ways of tackling biases in FGM measurement. This sort of rigorous evidence is crucial to drive policy conversations at a national level.

In Burkina Faso, for example, FGM among women of reproductive age has declined from 76% in 2010 to 56% in 2020. However, we cannot stop there. Through the Joint Program on the Elimination of FGM, we will continue to leverage rigorous evidence to inform the future design of programming. In a context of funding constraints, fragility, and climate stress, the task of eliminating FGM is daunting. But progress towards zero depends on evidence. Measuring FGM well is not an “add-on”—it’s foundational to getting to zero.

About the authors

The authors of this blog are Josué Ango, Néné Barry, Horace Gninafon, Fatoumata Ki, Achille Mignondo Tchibozo, Amber Peterman, Daouda Sako, Manahil Siddiqi, and Florent Somda (listed in alphabetical order).

Their affiliations are:

- UNICEF Burkina Faso: Josué Ango and Daouda Sako

- UNICEF Evaluation Office: Horace Gninafon and Amber Peterman

- UNICEF Office of Strategy and Evidence – Innocenti: Manahil Siddiqi

- UNFPA Burkina Faso: Néné Barry, Fatoumata Ki and Florent Somda

- La Société de Développement International: Achille Mignondo Tchibozo

Authors thank colleagues for various suggestions, inputs and conversations, including as part of the UNICEF-led Impact Catalyst Fund (ICF) on Child Marriage and Social Norms that sparked interest in further exploring FGM measurement in impact evaluations.